Artist Kãƒâ¤the Kollwitz Used Art as a Means of Working Through Her Sorrow Following the Death of a C

The middle remembers everything it loved and gave away,

everything it lost and found once more, and everyone

it loved, the centre cannot forget.

– Joyce Sutphen, "What the Eye Cannot Forget"

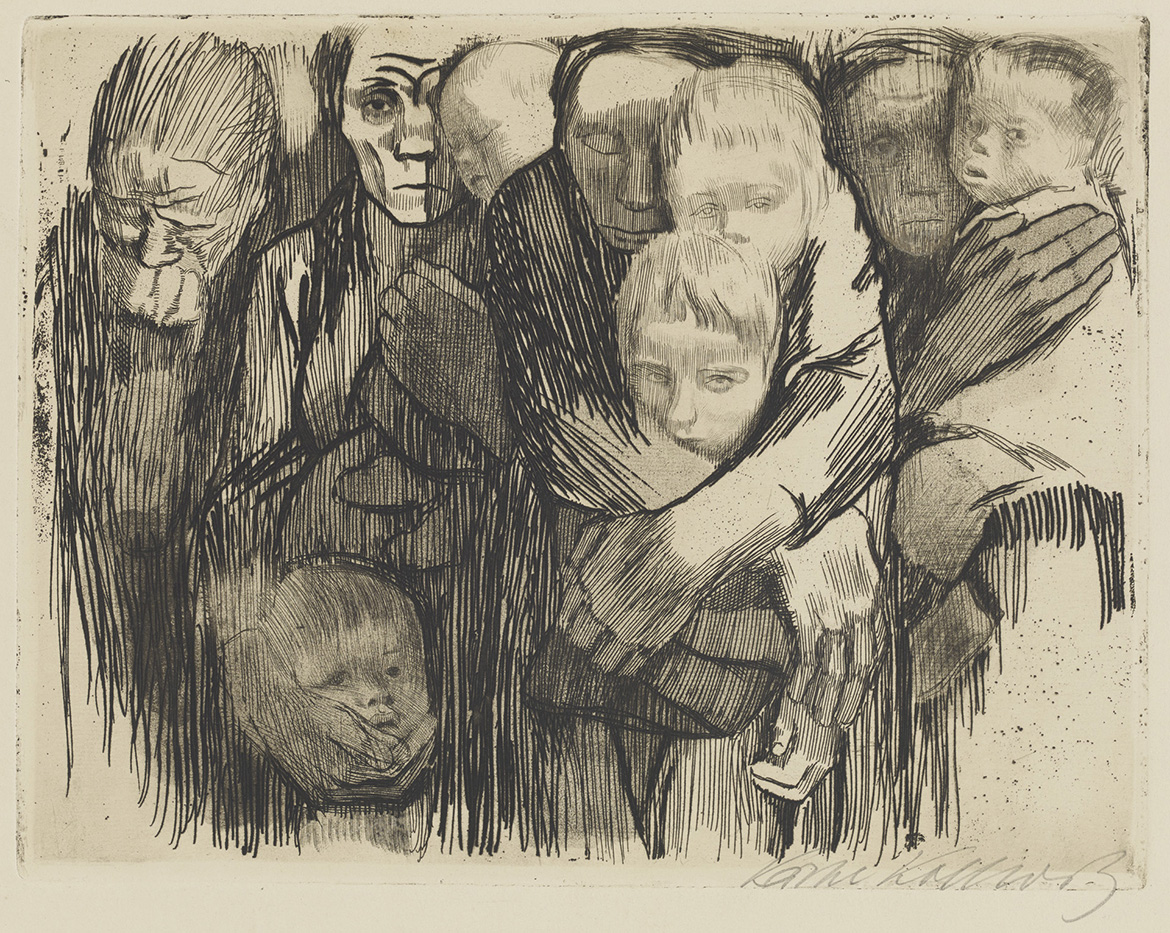

Käthe Kollwitz's lithograph The Mothers makes me long for a child. The German language creative person, working during both world wars, depicts a group of mothers continuing in a huddle; at that place are babies, toddlers, and young children in the group, safely protected behind the heavy limbs and hands of their mothers. The mothers merge, as if they are one mass force of protection and sorrow. One mother tightly grips her two children with her artillery; her head falls into the taller child'south head, her eyes shut as if she is relieved or weary. It is a portrait of desperate mother-dearest. Fifty-fifty though this 1920 lithograph wasn't created to promote motherhood—it was used every bit an anti-war poster—information technology makes me think that motherhood is a primordial part of being a adult female. The way these mothers interact with their children is deeply moving, pointing to an intense connectedness between them.

Epitome: Mothers, rejected beginning version of sheet six in the series »War«, 1918, line etching, sandpaper and soft ground with imprint of laid paper and bundle of needles, Kn 137 Ii (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

In a bronze sculpture of the same composition done in 1937, the effect is even more dramatic. The Tower of Mothers shows a group of mothers standing in a circle, facing outward with their arms joined. Their bodies form a protective barrier against annihilation that would try to harm their children. It could exist war, hunger, or poverty. Even the proper noun, Tower of Mothers, evokes the impression of a formidable force. Nil will come between them and their children.

Image: Tower of Mothers, 1937_1938 Statuary, Seeler 35 Two.B.1 (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

As I circle this sculpture in the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Berlin, this impenetrability draws me in. The force of the mothers' honey oozes out of this solid mass of metal. It pulls at my eye and makes me desire to have a child. Until and then, I'd been clashing about motherhood, thinking I could take it or exit it. After seeing Kollwitz'south work, I wasn't certain I could be so cavalier. I begin to wonder if I am missing out on one of life's slap-up experiences.

At the time Kollwitz sculpted it, the slice was to be part of an exhibition of works from artists in the Klosterstrasse neighborhood in Berlin in the belatedly 1930s. Kollwitz'south friend and fellow artist Otto Nagel wrote: "It is a strong, self-contained work, compactly designed, in which she used a motif she had oft depicted graphically, mothers defending their children. These women are militant, full of conclusion, ready to protect small and helpless creatures." The Nazis removed the piece from the exhibition, saying that mothers had no need to defend their children considering they lived in the era of the Tertiary Reich, where the Country protected children. Nagel wrote: "This must surely exist the superlative of cynicism, when one realizes that just a fiddling afterward, these aforementioned brown-shirted barbarians drove millions of young people ruthlessly to their death." Past the time she completed this work, Kollwitz had already lost a son in World State of war I and would lose her grandson in Globe War II.

Her work aptly puts an image to the feminist maxim that says the personal is political. Kollwitz is primarily known for her raw depictions of war and suffering, but her portrayals of maternity are what I find gripping. The emotional weight of her work catches me and makes me ponder the joy and sorrow of motherhood. Mothers dominate her work. They are protectors, sufferers, and nurturers; they are beings whose motherhood seems to fuel a supernatural kinetic energy—an energy crazy with life and loss.

In another sculpture, but titled Group, Kollwitz depicts a mother surrounding, well-nigh engulfing, her children with her arms. The female parent is sitting with her legs aptitude upwards, her back hunched over, and her face partially buried in the faces of her two children. The children, a babe and a toddler, sit down cradled in her arms, which reach effectually them then that her hands touch in front end of her. Certainly this could be a mother simply expressing beloved to her children. But there is something more than to this work. This is a woman who is desperate for her children, so much so that she wants to bring them back into herself where she can keep them safe. Psychotherapist Janna Malamud Smith describes this type of mother-love: "When a mother attaches to her children, her dear encircles them like a spider web of filaments that accomplish across physical separateness and link her feelings—her very nerve endings—to their rubber and well-being."

Epitome: Mother with two Children, 1932-1936 Statuary, 760 (h) 850 (w) 800 (d) mm, Seeler 29 I.B.half-dozen. (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

Does motherhood give a woman an impenetrable bond to another human? Kollwitz makes me think then. That bond also brings intense vulnerability. Vulnerability and impenetrability are at war in her mothers, contradictory forces that fight for dominance, with little uncontested ground.

In my ain ambivalence about motherhood, I'd allow fourth dimension and circumstances, instead of desire, determine my fate. I married in my mid-thirties and never considered having a child earlier and so. My childless state was not the norm in a earth where maternity seems inevitable. But I never had the intense longing for a child that and so many women described to me. Something changed when I met Kollwitz's mothers. I wanted to have the connection that I saw displayed in these works, that intense, all-consuming kind of love that makes everything else seem unimportant.

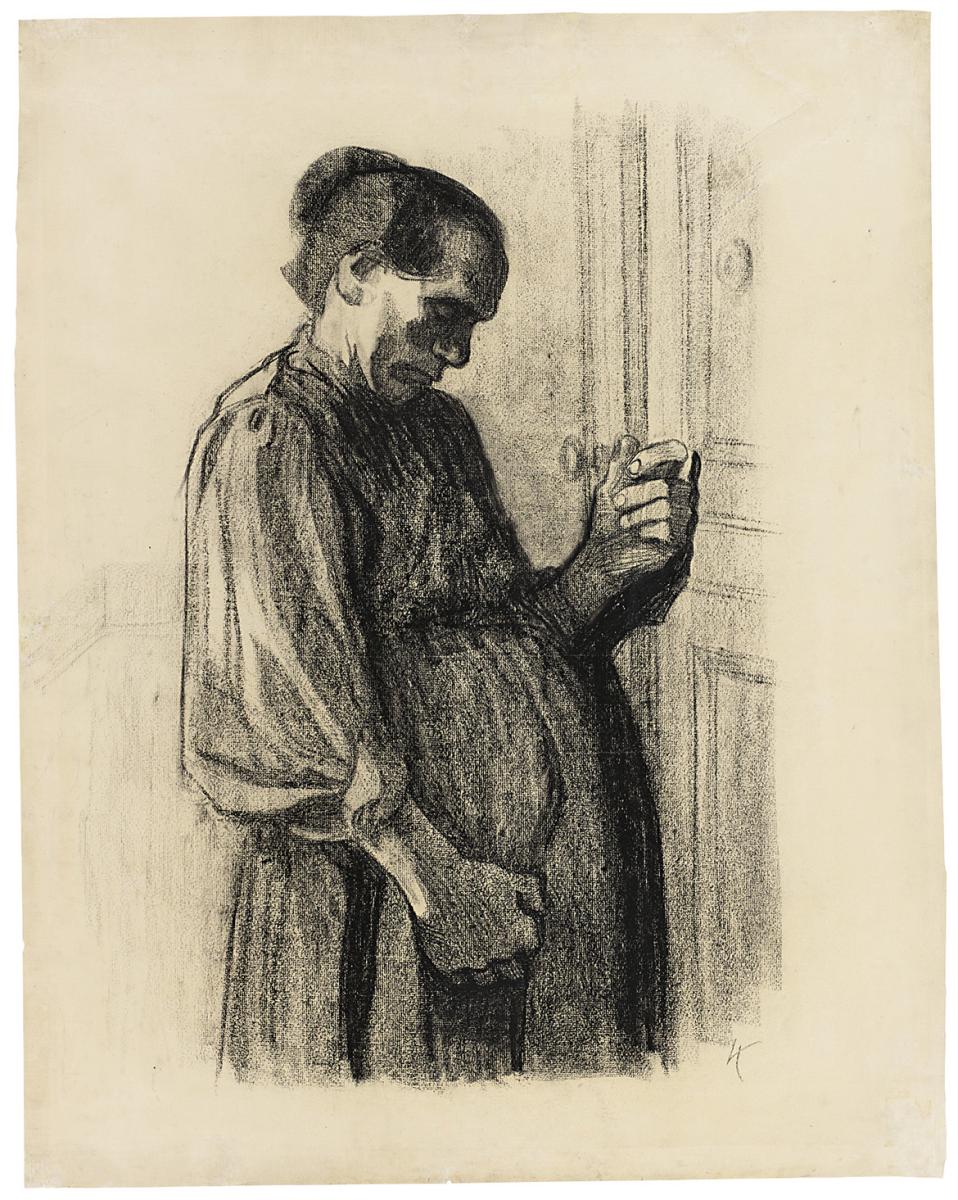

Image: At the Doctor's, sheet 3 of the series »Images of Misery«, 1908/1909 Black crayon on Ingres paper, NT 475 (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

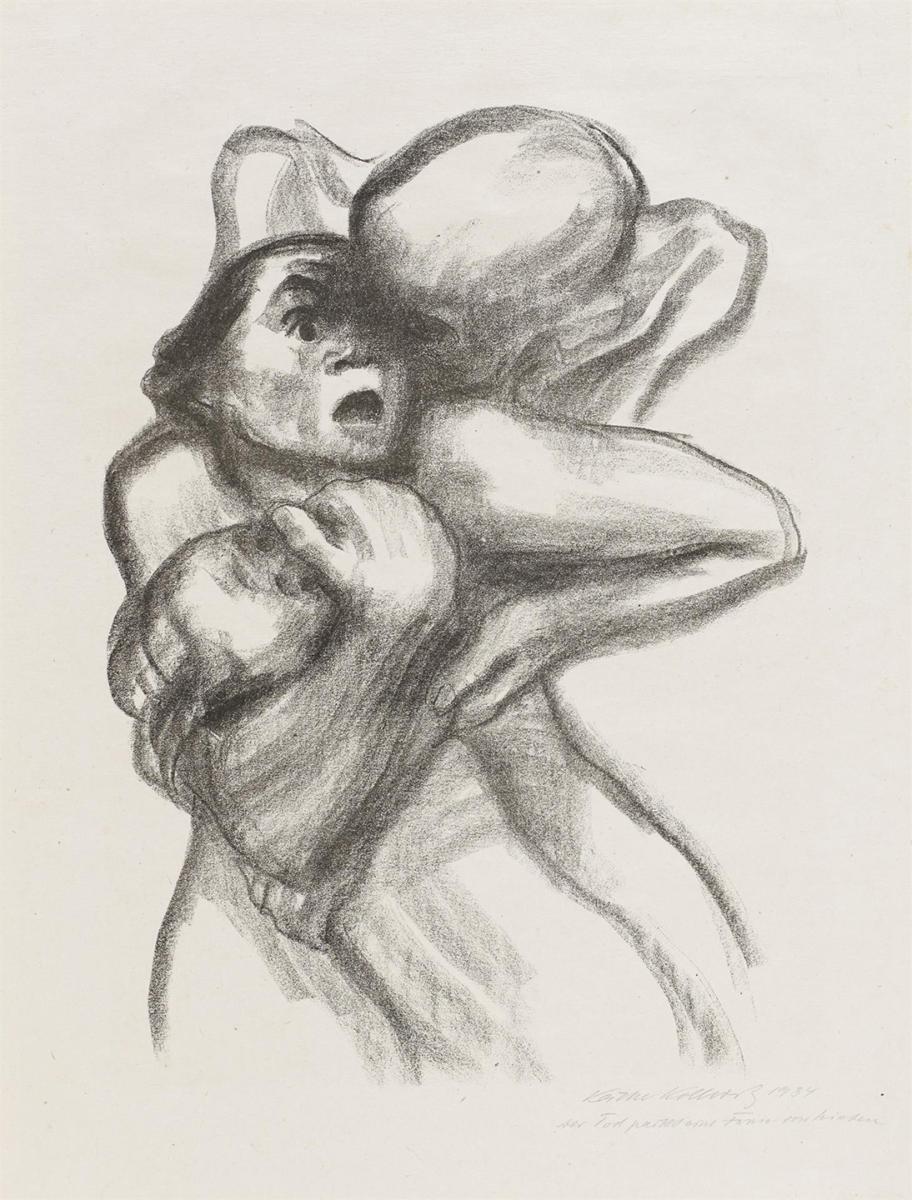

Kollwitz uses mothers to convey the deepest human emotions and experiences: anguish, hopelessness, joy, weariness, peace, anger, relief, fear, resignation, emptiness, and love. These are works in diverse mediums: charcoal drawings, lithographs, etchings, and woodcuts. Their somber bailiwick thing fuses with Kollwitz'south colorless depictions, blackness and white contrasting sharply with each other. In the dark and detailed lithograph Poverty, a mother leans over her small-scale child'due south bed, her head in her hands, her despair clear. Another, Portraits of Misery, III, a pregnant woman is shown in profile, knocking on a door. She could be seeking assist in the form of money, shelter, or food. In the print Decease and the Woman, a naked, muscular woman is struggling confronting the figure of death who grasps her from behind, his skeletal frame starting to wrap around her, as her young kid reaches upwards at her chest, trying to climb up her body. The rough woodcut Hunger shows dark skeletal figures, a mother with her bony hand covering her upturned face, while on her lap lies a dead kid. In the woodcut The Victim, a naked female parent holds up her newborn baby; they stand confronting a nighttime circular groundwork that engulfs them.

Image: Death seizes a Woman, sheet four of the series »Death«, 1934 Crayon lithograph, Kn 267 a (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

These mothers make me gasp in astonishment and sorrow. That hurting is at once real and gripping. Malamud Smith writes, "[M]other beloved is and then strong that it reaches beyond the human into some other realm of feeling; its intensity has a life of its ain, which overtakes women and creates an almost incomprehensible land of mind." Kollwitz captures this intensity with a sparseness befitting the drastic sadness of her characters.

Her work isn't what I would call conventionally beautiful. Nearly of her prints are shades of black and white; she was mainly a graphic artist. She gave upwards studying painting early in her training, saying that color was her stumbling block. In her piece of work few background flourishes telephone call my attention from the central subject of her works; there are no colors to get lost in; my optics don't move around the images, merely axle into the heart, into the face of the female parent, the central being, who pulls me in. Her sculptures likewise are blank, providing just enough shapes, hollows, and ridges to create heavy forms, weighted down with life's sorrows.

One of Kollwitz's favorite artists was Michelangelo. She made a drawing of The Pieta, following Michelangelo'due south famous sculpture in the St. Peter'south Cathedral in Rome, merely her rendition is starkly different. Michelangelo's Pieta is a work of devotion; Kollwitz's, a portrait of a mother and child.

Prototype: Woman with dead Child, 1903 Line etching, drypoint, sandpaper and soft basis with imprint of ribbed laid newspaper and Ziegler's transfer paper, Kn 81 8 a (c) Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln

Kollwitz'south Pieta draws on my emotions much more heavily. The mother is large and almost grotesque; she has none of the loveliness of Michelangelo'south Mary. She bends her body over to grasp the trunk of her dead child. Her head rests on his chest while her muscular arms and manly hands cling to the lifeless body. Except for a cloth that drapes the adult female's lap, all other elements that might distract me from the mother's loss accept been removed. This is ane of the few works where Kollwitz used colour, but nonetheless, the color is minimal. The background is night turquoise, and she uses thin strokes to highlight lines of skin and musculus. Heavy, dark lines correspond the mother's grim-fix mouth and closed eyes. This portrayal is one of sorrow and devastating, lasting loss.

The emotion in her Pieta nigh scares me abroad from maternity. The depth of pain that this mother feels is something I don't know if I can endure. When I contemplate having a child of my own, I wonder if this love will break me as information technology has broken Kollwitz's mothers.

I struggle to alive my life without fear, simply it'southward there. Possible dangers abound—illnesses, accidents, and all manners of impairment seem to be lurking around every corner. Motherhood magnifies this fear. Malamud Smith writes, "…there is an enlarged sense of vulnerability, personal and social, created by becoming a mother—and accepting the intimate mission of keeping a dependent being alive." We are all vulnerable, but motherhood somehow puts that vulnerability right in front of yous; it makes mortality more vivid. I've pondered this for years and even after finally being in the position to have a child, I wondered if information technology was something I could do. I've weighed what I might miss by never becoming a mother against what I would lose if something happened to my child. I am starting to believe that maternity may exist worth it, that the fearfulness may exist overshadowed past joy.

Kollwitz has trapped me with tragedy, snared me with sorrow. When her parents asked her why she portrayed the night side of life, she had no reply. She writes in her diary, "The joyous side simply did non appeal to me." As well living through her own suffering, Kollwitz felt the sadness and suffering of the people effectually her. She observed many poor mothers and their children in her married man's medical dispensary, which was located in a working-class neighborhood in northeastern Berlin. His patients were tailors and their families. Her husband's practice was ane of the first types of socialized medicine to be implemented in Frg and was a precursor of our modernistic medical insurance.

Many of the women who came to her hubby's clinic were the models or inspiration for her work. They weren't her subjects just because they would assist her create a political message; she said she chose them because she found them beautiful. In her diaries, she writes of being grieved and tormented by the problems of working-class women. They were poor. Some had been abused past their husbands. Their children were sick. They were non happy women. These women connected her to a life she considered real. "…[P]ortraying them again and over again opened a safety-valve for me; it made life bearable." She connected with them in her work through her feel of motherhood; it's the same theme that I observe and so appealing. Mayhap portraying bug through motherhood makes them more than palatable, more than easily grasped by anyone. Everyone has had a biological mother or father, many people are parents themselves; people looking at her work understand the power of human being connection. Biographer Carl Zigrosser said that she looked at life not equally a woman, but as a mother: "Her fidelity was not to Aphrodite just to the Eternal Female parent."

Kollwitz was tangentially a office of an fine art move, Expressionism, that constitute a home amongst German language artists. Expressionists distorted or caricatured their subjects in ways to "express" an emotion, similar love, admiration, fear, or sadness.

Expressionist fine art was oftentimes non "beautiful" fine art. Expressionists showed their subjects equally "ugly" if that would convey a message. As fine art historian East. H. Gombrich explains: "[T]he Expressionists felt so strongly about human suffering, poverty, violence and passion, that they were inclined to call back that the insistence on harmony and beauty in fine art was merely born out of a refusal to exist honest."

Expressionism aroused the acrimony and vindictiveness of the "little human being," Gombrich says. When the Nazis came to power, they banned this type of art and exiled those artists or forbade them to work.

For Expressionists, the message became more important than the subject field, so artists began experimenting with the effects of tone and shape at the expense of the subject affair. This is where Kollwitz differed from her contemporaries; she wanted her fine art to be accessible to anyone. She wanted her art to alter the earth. Art historians Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin write, "…she increasingly came to come across Expressionism as a rarefied art of the studio, divorced from social reality. 'I am convinced,' she wrote in a diary of 1908, 'that there must exist an understanding between the artist and the people such every bit there always used to be in the best periods in history.' " Kollwitz insisted on a social function of art. She wanted her art to connect with the people who looked at it. She certainly succeeded with me. As I stared at her mothers in that Berlin gallery, I plant myself near overtaken by the emotion of her work.

Kollwitz's art depicts non only the earth she saw, simply her attempts to bear upon information technology. "She was a searcher to the end," Zigrosser says. She wanted her art to change the despair and destruction surrounding her. In her diary she wrote: "One can say it a grand times that pure art does non include within itself a purpose. As long equally I can work, I want to accept an effect with my art." Her relentlessness to brand a difference with her fine art changed me, slowly moving me from ambivalence to want.

Kollwitz saw the world through the dual lenses of female parent and artist. With her work, she merged the two. She watched other mothers suffer considering of social ills like poverty, exploitation, and state of war. She suffered as a female parent: Her son and grandson were casualties of ii different wars. It is this loss that brings out the depth of feeling in her work; information technology's a special kind of female parent-loss, a grief that is possibly harder to comport than other types of grief. In her diaries, she writes of how her work continued her to her son who had died, and the grief pushed her on to piece of work: "I might make a hundred such drawings and yet I do not get whatever closer to him. I am seeking him. As if I had to find him in the work."

She tapped into a collective loss that transcended class, nationality, ethnicity, and generations. Looking at her work, I wonder, can motherhood brand you more empathetic? More donating? Less myopic? Kollwitz, with what Nagel calls her "all-embracing female parent love," makes me retrieve and so. Of that dearest, he writes: "It hovers near her work like a symbol of goodness, it gives us hope that we shall notice a refuge." A refuge in suffering together, in solidarity, in naming the hurting.

I danced effectually this pain of mother-loss without having children, fearing losing something I didn't even have. Withal when I await at Kollwitz's mothers, I feel their overwhelming loss, their fear of impairment. I slowly begin to think that peradventure, just peradventure, information technology is a worthwhile cede—my fearfulness for indescribable dearest and connection.

Motherhood asks you to care almost another; to sacrifice for someone else'due south well-being. Possibly it feels more natural doing this for one you brought through the birthing process or waited for months to adopt. Maybe maternity provides women with a sense of purpose. Simone de Beauvoir wrote in Second Sexual practice: "Like the woman in honey, the mother is delighted to experience herself necessary." Kollwitz's mothers are more than necessary; they are all about cede. But it's more a cede of fourth dimension or piece of work or energy. It is a loss of emotion, of self, of control; it is the willingness to lose yourself in another wholly dependent being, a willingness to risk the loss but a hope that you won't have to. It is accepting pleasure and pain, delight and sorrow. Maybe these tradeoffs shouldn't terminate me; in fact, maybe they'll make my life richer.

Motherhood was one fashion for Kollwitz to find a connectedness through her art. Through her mothers, Kollwitz shows every emotion, appeals to the bones urges of human experience. She wrote: "Only the proficient artists who follow after genius—and I count myself among these, have to restore the lost connection once more. A pure studio art is unfruitful and frail, for anything that does non class living roots—why should it exist at all." Kollwitz fabricated living roots through her female parent art.

And that is how she found me, enticed me with a desire to dear more than deeply and open myself upwards to the hurting and cede of motherhood. I call up of her mothers now equally I rock my baby girl to sleep, marveling at her life and the style she's filled my heart. And when I worry about how I will take care of this kid, I mentally revisit Kollwitz's sculpture in that Berlin museum, to the place where I was first ensnared, to the place where Kollwitz'southward living roots grew out of her mothers, through the base of her sculpture, beyond the floor, and around my feet. They twined around my legs, up through my womb, and tightly circled my heart. They slipped upwardly around my neck and into my ears, and whispered, "Yes!"

Source: https://northamericanreview.org/open-space/nonfiction-brenda-van-dyck

0 Response to "Artist Kãƒâ¤the Kollwitz Used Art as a Means of Working Through Her Sorrow Following the Death of a C"

Postar um comentário